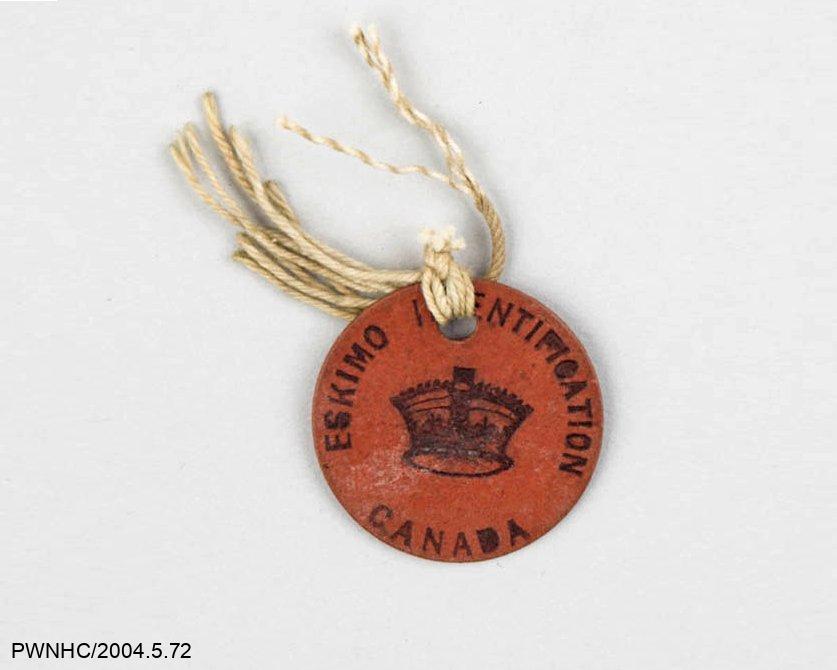

1944

W Tags

Indigenous names presented a challenge when the Government of Canada began to enumerate the people living in the North. Government forms required first names and surnames, which wasn’t common practice among the Indigenous people. The Inuit/Inuvialuit tradition of naming was more flexible, allowing for life changes and family and ancestorial connections. Northerners were eligible for Canada’s new family allowance and old age programs, but European-style names were required on the forms.

Canada’s solution to this issue would create additional problems. In 1944, Inuit were assigned “Eskimo Identification Numbers” People living east of Gjoa Haven were assigned the letter E, followed by a number, and those to the west were given the letter W. The number represented the region, the community, and the individual. Each person received a disc stamped with their number to be shown as identification at the trading posts and to the RCMP.

In the late 1960s, the Government in the Northwest Territories started recognizing that the derogatory, cumbersome, and antiquated disc system should be replaced with government-issued birth certificates. The push for the imposition and acceptance of Canadian naming systems moved across the Arctic. Abe Okpik, an Inuvialuk from Aklavik, was tasked with travelling to every settlement of the Arctic to help families pick names that would be more suitable for government forms. He remembers Stu Hodgson stopping him at the airport and assigning him his new job. “Well, Abe, you have to get rid of these disc numbers; they’ve got to go!”

The Canadian government stopped issuing the identification discs in 1971, but the imposition of colonial names continues.