1934

Yellowknife Gold

Indigenous people living around Yellowknife Bay “discovered” gold long before white settlers staked the first productive claims in the 1930s. The Yellowknives Dene tell the story of Liza Crookedhand, a Dene Elder, who was camped near the Wıìlıìdeh (Yellowknife River) for the summer fishery when a white man came into her tent. He spotted a rock on her stove that her sister Mary Fishbone had picked up while berry picking not far from her camp. The white man offered to trade her some new stove pipe for the rock.

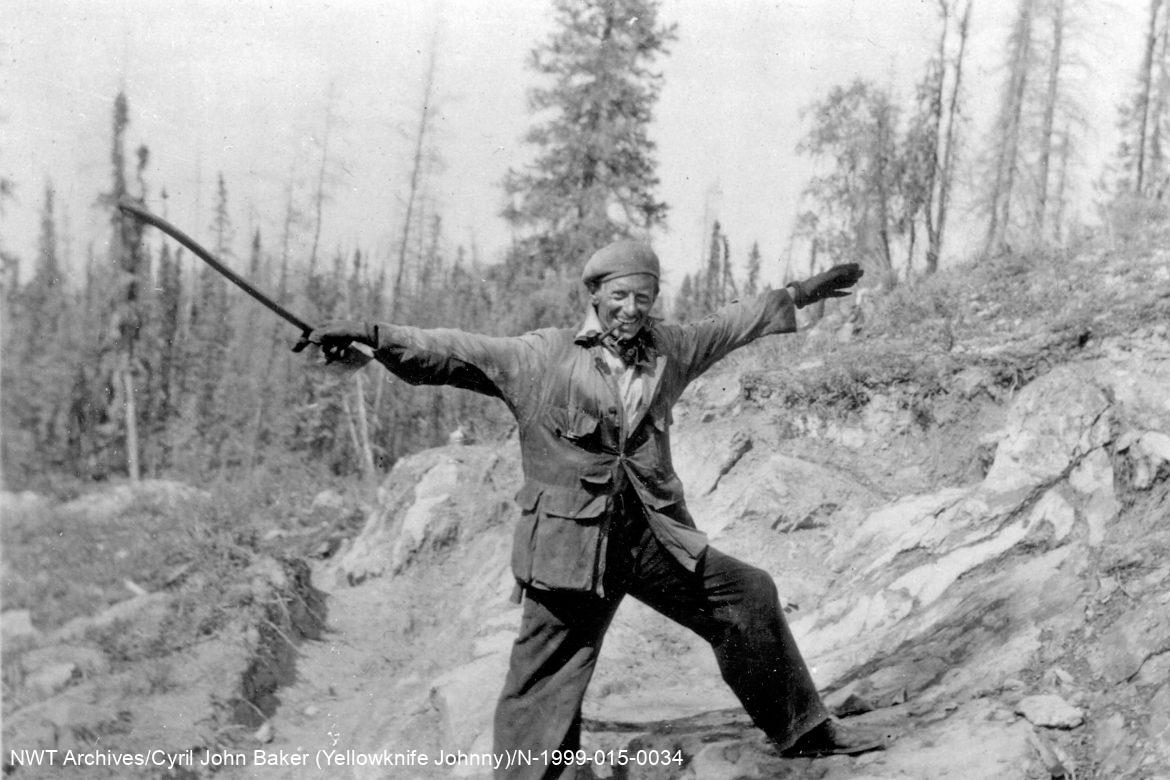

Prospectors had been searching for gold in the Northwest Territories for many years. Small amounts of gold were observed on the north side of Great Slave Lake in 1898 during the Klondike Gold Rush, but it wasn’t until the late 1920s-1930s that prospecting began to take off. In 1933 a bush plane dropped Herb Dixon and Johnny Baker off near the headwaters of the Coppermine River, and they slowly worked their way south, looking for signs of gold. They staked gold showings 50 kilometres north of Yellowknife, and Johnny Baker returned to the area in 1934 with a new partner Hughie Muir. Setting up camp, they discovered a quartz vein “lousy with visible gold” on the east side of Yellowknife Bay. This rich find, the first substantial gold discovery in the area, became the Burwash gold mine operating from 1935-1936. Due to the importance of Johnny Baker’s find, 1934 marks the birth of the city of Yellowknife, although a town would not be started until a few more years later.

Johnny Baker later went on to stake the gold claims at what became Giant Mine and may have been the prospector that met with Liza Crookedhand at her tent on the Yellowknife River.

In response to the gold activity at Yellowknife Bay, the Geological Survey of Canada sent Alfred Jolliffe, with 14 young students, to map 20,000 square kilometres on the north side of Great Slave Lake in the summer of 1935. Geologic maps of this area were needed to assist prospectors who were coming to look for more gold.

Among the early prospectors, Vic Stevens, Don MacLaren, and Ed McLellan represented the AX Syndicate. They met with Jolliffe to look at some preliminary geologic maps and then asked if he could recommend any promising areas to conduct one last prospecting trip before freeze-up. Jolliffe suggested they meet up with one of his students, Norman Jennejohn, who was mapping the west side of Yellowknife Bay. The three prospectors joined Jennejohn on his survey and came across a white quartz vein loaded with gold north of current-day Jackfish Lake. Borrowing the government axe, the prospectors began to stake a claim!

It was now the end of September 1935, and winter was fast approaching. Word got out to other prospectors packing up and heading south for the season in Fort Smith of another gold strike at Yellowknife. Consolidated Mining & Smelting (Cominco) decided to fly their prospectors back and tie onto the AX Syndicate claims on the west side of Yellowknife Bay. Stakers worked furiously as October snows fell onto the taiga landscape. Nobody knew what might lay beneath, yet under Cominco’s claims proved to be a massive gold deposit; the Con Mine poured its first gold bar in 1938.